The first-ever international conference on the contentious topic of “overshoot” was held last week in a palace in the small town of Laxenburg in Austria.

The three-day conference brought together nearly 200 researchers and legal experts to discuss future temperature pathways where the Paris Agreement’s “aspirational” target to limit global warming to 1.5C is met “from above, rather than below”.

Overshoot pathways are those which exceed the 1.5C limit – before being brought back down again through techniques that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The conference explored both the feasibility of overshoot pathways and the legal frameworks that could help deliver them.

Researchers also discussed the potential consequences of a potential rise – and then fall – of global temperatures on climate action, society and the Earth’s climate systems.

Speaking during a plenary session, Prof Joeri Rogelj, a professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, said that “moving into a world where we exceed 1.5C and have to manage overshoot” was an exercise in “managing failure”.

He said that it was “essential” that this failure was acknowledged, explaining that this would help set out the need to “minimise and manage” the situation and clarify the implications for “near-term action” and “long-term [temperature] reversal”.

Below, Carbon Brief draws together some of the key talking points, new research and discussions that emerged from the event.

Defining overshootMitigation ambition and 1.5C viabilityCarbon removalImpacts of overshootAdaptationLegal implications and loss and damageCommunication challenges and next steps

Defining overshoot

The study of temperature overshoot has grown in recent years as the prospects of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C have dwindled.

Conference organiser Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner – a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) – explained the event was designed to bring together different research communities working on a “new field of science”.

He told Carbon Brief:

“If we look at [overshoot] in isolation, we may miss important parts of the bigger picture. That’s why we also set out the conference with very broad themes and a very interdisciplinary approach.”

The conference was split between eight conference streams: mitigation ambition; carbon dioxide removal (CDR); Earth system responses; climate impacts; tipping points; adaptation; loss and damage; and legal implications.

There was also a focus on how to communicate the concept of overshoot.

In simple English, “overshoot” means to go past or beyond a limit. But, in climate science, the term implies both a failure to meet a target – as well as subsequent action to correct that failure.

Today, the term is most often deployed to describe future temperature trajectories that exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit – and then come back down.

(In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) fifth assessment cycle, completed in 2014, the term was used to describe a potential rise and then fall of CO2 concentrations above levels recommended to meet long-term climate goals. A recent “conceptual” review of overshoot noted this was because, at the time, CO2 concentrations were the key metric used to contextualise emissions reductions).

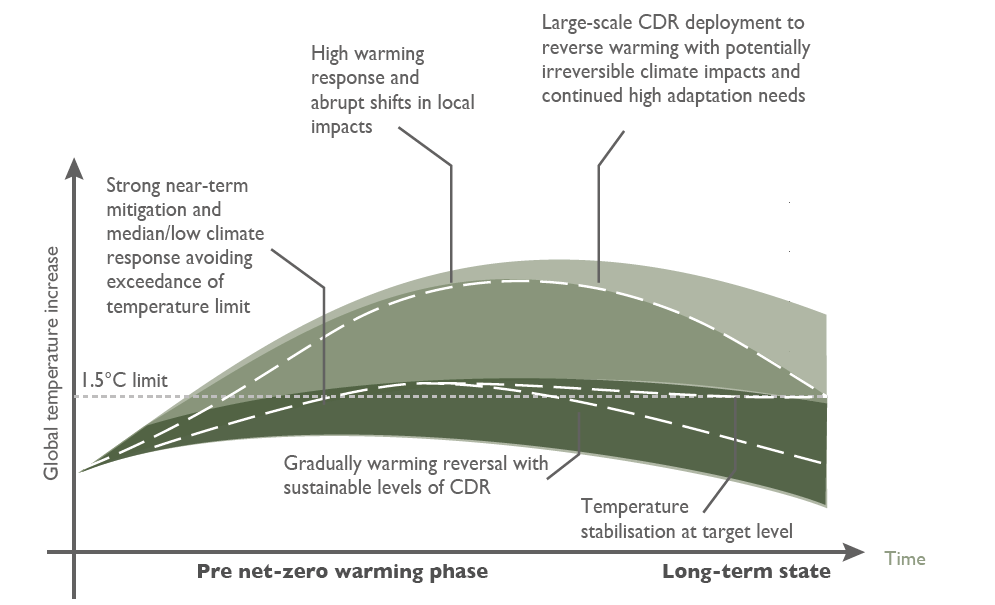

The plot below provides an illustration of three overshoot pathways. The most pronounced pathway sees global temperatures rise significantly above the 1.5C limit – before eventually falling back down again as carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere at scale.

In the second and third pathways, global temperature rise breaches the limit by a smaller margin, before either falling enough just to stabilise around 1.5C, or dropping more dramatically due to larger-scale carbon removals.

Credit: Amended from Schleussner et al (2024).

In an opening address to delegates, Prof Jim Skea, who is the current chair of the IPCC, acknowledged the scientific interpretation of overshoot was not intuitive to non-experts.

“The IPCC has mainly used two words in relation to overshoot – “exceeding” and “limiting”. To a lay person, these can sound like opposites. Yet we know that a single emissions pathway can both exceed 1.5C in the near term and limit warming to 1.5C in the long term.”

Noting that different research communities were using the term differently, Skea urged researchers to be precise with terminology and stick to the IPCC’s definition of overshoot:

“We should give some thought to communication and keep this as simple as possible. When I look at texts, I hear more poetic words like “surpassing” and “breaching”. I would urge you to keep the range of terms as small as possible and make sure that we’re absolutely using them consistently.”

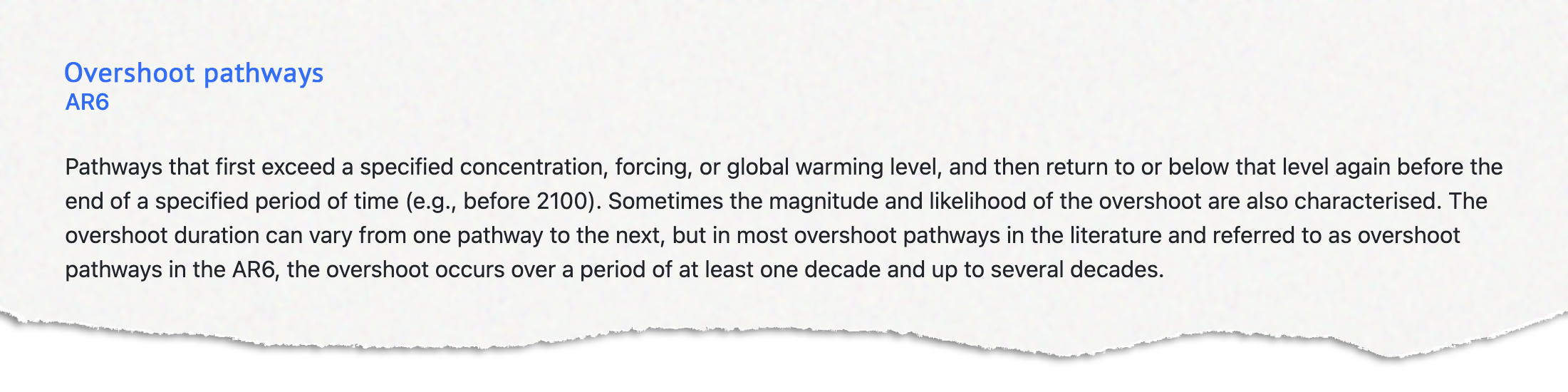

In the glossary for its latest assessment cycle, AR6, the IPCC defines “overshoot” pathways as follows:

IIASA’s Schleussner stressed that not all pathways that go beyond 1.5C qualify as overshoot pathways:

“The most important understanding is that overshoot is not any pathway that exceeds 1.5C. An overshoot pathway is specific to this being a period of exceedance. It is going to come back down below 1.5C.”

Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

Perhaps the most prominent topic during the conference was the implications of overshoot for global ambition to cut carbon emissions and the viability of the 1.5C limit.

Opening the conference, IIASA director general Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber shared his personal view that “1.5C is dead, 2C is in agony and 3C is looming”.

In a pre-recorded keynote speech, Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s minister for climate change, called for a rejection of the “normalisation of overshoot” and argued that “we must treat 1.5C as the absolute limit that it is” and avoid backsliding. He added:

“Minimising peak warming must be our lodestar, because every tenth of a degree matters.”

Prof Skea opened his keynote with some theology:

“I’m going to start with the prayer of St Augustine as he struggled with his youthful longings: ‘Lord grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.’ And it does seem that this is the way that the world as a whole is thinking about 1.5C: ‘Lord, limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but not yet.’”

Referencing the “lodestar” mentioned by Regenvanu, Skea warned that it is light years away and, “unless we act with a sense of urgency, [1.5C is] likely to remain just as remote”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief on the sidelines of the conference, Skea added:

“We are almost certain to exceed 1.5C and the viability of 1.5C is now much more referring to the long-term potential to limit it through overshoot.”

Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the framing of 1.5C in the conference is “one that further solidifies 1.5C as the long-term limit and, therefore, provides a backstop against the idea of reducing or backsliding on targets”.

If warming is going to surpass 1.5C, the next question is when temperatures are going to be brought back down again, Schleussner added, noting that there has been no “direct” guidance on this from climate policy:

“The [Paris Agreement’s] obligation to “pursue efforts” [to limit global temperature rise by 1.5C] points to doing it as fast as possible. Scientifically, we can determine what this means – and that would be this century. But there’s no clear language that gives you a specific date. It needs to be a period of overshoot – that is clear – and it should be as short as possible.”

In a parallel session on the “highest possible mitigation ambition under overshoot”, Prof Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, outlined how the recent ruling from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) provides guidance to countries on the level of ambition in their climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs). He explained:

“[The ruling] highlights that the level of NDC ambition is not purely discretionary to a state and that every state must do its utmost to ensure its NDC reflects the highest possible ambition to meet the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal.”

Rogelj presented some research – due to be published in the journal Environmental Research Letters – on translating the ICJ’s guidance “into a framework that can help us to assess whether an NDC indeed is following a standard of conduct that can represent the highest level of ambition”. He showed some initial results on how the first two rounds of NDCs measure up against three “pillars” covering domestic, international and implementation considerations.

In the same session, Prof Oliver Geden, senior fellow and head of the climate policy and politics research cluster at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and vice-chair of IPCC Working Group III, warned that the concept of returning temperatures back down to 1.5C after an overshoot is “not a political project yet”.

He explained that there is “no shared understanding that, actually, the world is aiming for net-negative”, where emissions cuts and CDR together mean that more carbon is being taken out of the atmosphere than is being added. This is necessary to achieve a decline in global temperatures after surpassing 1.5C.

This lack of understanding includes developed countries, which “you would probably expect to be the frontrunners”, Geden said, noting that Denmark is the “only developed country that has a quantified net-negative target” of emission reductions of 110% in 2050, compared to 1990 levels. (Finland also has a net-negative target, while Germany announced its intention to set one last year. In addition, a few small global-south countries, such as Panama, Suriname and Bhutan, have already achieved net-negative.)

Geden pondered whether developed countries are a “little bit wary to commit to going to net-negative territory because they fear that once they say -110%, some countries will immediately demand -130% or -150%” to pay back a larger carbon debt.

Carbon removal

To achieve a decline in global temperatures after an initial breach of 1.5C would require the world to reach net-negative emissions overall.

There is a wide range of potential techniques for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, such as afforestation, direct air capture and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Captured carbon must be locked away indefinitely in order to be effective at reducing global temperatures.

However, despite its importance in achieving net-negative emissions, there are “huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal”, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief. He continued:

“As it’s very clear from the themes of this conference, we don’t altogether understand how the Earth would react in taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. We don’t understand the nature of the irreversibilities. And we don’t understand the effectiveness of CDR techniques, which might themselves be influenced by the level of global warming, plus all the equity and sustainability issues surrounding using CDR techniques.”

Skea notes that the seventh assessment cycle of the IPCC, which is just getting underway, will “start to fill these knowledge gaps without prejudging what the appropriate policy response should be”.

Prof Kristie Ebi, Dr Jonathan Donges, Prof Debra Roberts, Prof Deliang Chen, Dr Matt Gidden, Dr Annika Högner and Dr Keywan Riahi at a plenary session at the Overshoot Conference. Credit: IIASA

Prof Nebojsa Nakicenovic, an IIASA distinguished emeritus research scholar, told Carbon Brief that his “major concern” was whether there would be an “asymmetry” in how the climate would respond to large-scale carbon removal, compared to its response to carbon emissions.

In other words, he explained, would global temperatures respond to carbon removal “on the way down” in the same way they did “on the way up” to the world’s carbon emissions.

Nakicenovic noted that overshoot requires a change in focus to approaching the 1.5C limit “from above, rather than below”.

Schleussner made a similar point to Carbon Brief:

“We may fail to pursue [1.5C] from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above. I think that’s also a key message and a very strong overarching message that’s going to come out from the conference that we see…that pursuing an overshoot and then decline trajectory is both an obligation, but it also is well rooted in science.”

Reporting back to the plenary from one of the parallel sessions on CDR, Dr Matthew Gidden, deputy director of the Joint Global Change Research Institute at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, also noted another element of changing focus:

“When we’re talking about overshoot, we have become used to, in many cases, talking about what a net-zero world looks like. And that’s not a world of overshoot. That’s a world of not returning from a peak. And so communicating instead about a net-negative world is something that we could likely be shifting to in terms of how we’re communicating our science and the impacts that are coming out of it.”

On the need for both CDR and emissions cuts, Gidden noted that the discussions in his session emphasised that “CDR should not be at the cost of mitigation ambition”. But, he added, there is still the question of how “we talk about emission reductions needed today, but also likely dependence on CDR in the future”.

In a different parallel session, Prof Geden also made a similar point, noting that “we have to shift CDR from being seen as a barrier to ambition to an enabler of even higher ambition, but not doing that by betting on ever more CDR”.

Among the research presented in the parallel sessions on CDR was a recent study by Dr Jay Fuhrman from the JGCRI on the regional differences in capacity to deploy large-scale carbon removal. Ruben Prütz, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, presented on the risks to biodiversity from large-scale land-based CDR, which – in some cases – could have a larger impact than warming itself.

In another talk, the University of Oxford’s Dr Rupert Stuart-Smith explored how individual countries are “depending very heavily on [carbon] removals to meet their climate targets”. Stuart-Smith was a co-author on an “initial commentary” on the legal limits of CDR, published in 2023. This has been followed up with a “much more detailed legal analysis”, which should be published “very soon”, he added.

Impacts of overshoot

Since the Paris Agreement and the call for the IPCC to produce a special report on 1.5C, research into the impacts of warming at the aspirational target has become commonplace.

Similarly, there is an abundance of research into the potential impacts at other thresholds, such as 2C, 3C and beyond.

However, there is comparatively little research into how impacts are affected by overshoot.

The conference included talks on some published research into overshoot, such as the chances of irreversible glacier loss and lasting impacts to water resources. There were also talks on work that is yet to be formally published, such as the risks of triggering interacting tipping points under overshoot.

Speaking in a morning plenary, Prof Debra Roberts, a coordinating lead author on the IPCC’s forthcoming special report on climate change and cities and a former co-chair of Working Group II, highlighted the need to consider the implications of different durations and peak temperatures of overshoot.

For example, she explained, it is “important to know” whether the impacts of “overshoot for 10 years at 0.2C above 1.5C are the same as 20 years at 0.1C of overshoot”.

Discussions during the conference noted that the answer may be different depending on the type of impact. For heat extremes, the peak temperature may be the key factor, while the length of overshoot will be more relevant for cumulative impacts that build up over time, such as sea level rise.

Similarly, if warming is brought back down to 1.5C after overshoot, what happens next is also significant – whether global temperature is stabilised or net-negative emissions continue and warming declines further. Prof Schleussner told Carbon Brief:

“For example, with coastal adaptation to sea level rise, the question of how fast and how far we bring temperatures back down again will be decisive in terms of the long-term outlook. Knowing that if you stabilise that around 1.5C, we might commit two metres of sea level rise, right? So, the question of how far we can and want to go back down again is decisive for a long-term perspective.”

One of the eight themes of the conference centred specifically on the reversibility or irreversibility of climate impacts.

In his opening speech, Vanuatu’s Ralph Regenvanu warned that “overshooting 1.5C isn’t a temporary mistake, it is a catalyst for inescapable, irreversible harm”. He continued:

“No level of finance can pull back the sea in our lifetimes or our children’s. There is no rewind button on a melted glacier. There is no time machine for an extinct species. Once we cross these tipping points, no amount of later ‘cooling’ can restore our sacred reefs, it cannot regrow the ice that already vanished and it cannot bring back the species or the cultures erased by the rising tides.”

As an example of a “deeply, deeply irreversible” impact, Dr Samuel Lüthi, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern, presented on how overshoot could affect heat-related mortality.

Using mortality data from 850 locations across the world, Lüthi showed how projections under a pathway where warming overshoots 1.5C by 0.1-0.3C, before returning to 1.5C by 2100 has 15% more heat-related deaths in the 21st century than a pathway with less than 0.1C of overshoot.

His findings also suggested that “10 years of 1.6C is very similar [in terms of impacts] to five years of 1.7C”.

Extreme heat also featured in a talk by Dr Yi-Ling Hwong, a research scholar at IIASA, on the implications of using solar geoengineering to reduce peak temperatures during overshoot.

She showed that a world where a return to 1.5C had been achieved through geoengineering would see different impacts from a world where 1.5C was reached through cutting emissions. For example, in her modelling study, while geoengineering restores rainfall levels for some regions in the global north, significant drying “is observed in many regions in the global south”.

Similarly, a world geoengineered to 1.5C would see extreme nighttime heat in some tropical regions that is more severe than in a 2C world with no geoengineering, Hwong added.

In short, she said, “this implies the risk of creating winners and losers” under solar geoengineering and “raises concerns about equity and accountability that need to be considered”.

After describing how overshoot features in the outlines of the forthcoming AR7 reports in his opening speech, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief that he expects a “surge of papers” on overshoot in time to be included.

But it was important to emphasise that a “lot of the science that people have been carrying out is relevant within or without an overshoot”, he added:

“At points in the future, we are not going to know whether we’re in an overshoot world or just a high-emissions world, for example. So a lot of the climate research that’s been done is relevant regardless of overshoot. But overshoot is a new kind of dimension because of this issue of focus on 1.5C and concerns about its viability.”

Adaptation

The implications of overshoot temperature pathways for efforts to prepare cities, countries and citizens for the impacts of climate change remains an under-researched field.

Speaking in a plenary, Prof Kristie Ebi – a professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Health and the Global Environment – described research into adaptation and overshoot as “nascent”. However, she stressed that preparing society for the impacts associated with overshoot pathways was as important as bringing down emissions.

She told Carbon Brief that there were “all kinds of questions” about how to approach “effective” adaptation under an overshoot pathway, explaining:

“At the moment, adaptation is primarily assuming a continual increase in global mean surface temperature. If there is going to be a peak – and, of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning? Do you change your planning? There are places, for instance when thinking about hard infrastructure, [where overshoot] may result in a change in your plan.”

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the scientific community was only just “beginning to appreciate” the need to understand and “quantify” the implications of different overshoot pathways on adaptation.

In a parallel session, Dr Elisabeth Gilmore, associate professor in environmental engineering and public policy at Carleton University in Canada, made the case for overshoot modelling pathways to take greater account of political considerations.

“Not just, but especially, in situations of overshoot, we need to start thinking about this as much as a physical process as a socio-political process…If we don’t do this, we are really missing out on some key uncertainties.”

Current scenarios used in climate research – including the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Representative Concentration Pathways – are “a bit quiet” when it comes to thinking about governance, institutions and peace and conflict, Gilmore said. She added:

“Political institutions, legitimacy and social cohesion continue to shift over time and this is really going to shape how much we can mitigate, how much we adapt and especially how we would recover when adding in the dimension of overshoot.”

Gilmore argued that, from a social perspective, adaptation needs are greatest “before the peak” of temperature rise – because this is when society can build the resilience to “get to the other side”. She said:

“Orthodoxy in adaptation [research] that you always want to plan for the worst [in the context of adaptation, peak temperature rise]… But we don’t really know what this peak is going to be – and we know that the politics and the social systems are much more messy.”

Dr Marta Mastropietro, a researcher at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, presented the preliminary results of a study that used emulators – simple climate models – to explore how human development might be impacted under low, medium and high overshoot pathways.

Mastropietro noted how, under all overshoot scenarios studied, both the drop to the human development index (HDI) – an index which incorporates health, knowledge and standard of living – and uncertainty increases as the peak temperature increases.

However, she said “the most important takeaway” from the preliminary results was around society’s constrained ability to recover from damage.

“This percentage of damages that are absorbed is always less than 50%. So, even in the most optimistic scenarios of overshoot, we will not be able to reabsorb these damages, not even half of them. And this is considering a damage function which does not consider irreversible impacts like sea level rise.”

Meanwhile, Dr Inês Gomes Marques from the University of Lisboa in Portugal, shared the results of an as-yet-unpublished study investigating whether the Lisbon metropolitan area holds enough public spaces to offer heatwave relief to the population under overshoot scenarios. The 1,900 “climate refugia” counted by researchers included schools, museums and churches.

Marques noted that most of the population were found to be within one kilometre of a “climate refugia” – but noted that “nuances” would need to be added to the analysis, including a function which considers the limited mobility of older citizens.

She explained that the researchers were aiming to “establish a framework” for this type of analysis that would be relevant to both the science community and municipalities tasked with adaptation. She added:

“The main point is that we need to think about this now, because we will face some big problems if we don’t”.

Delegates attend a poster session at the Overshoot Conference. Credit: IIASA

Legal implications and loss and damage

Significant attention was given throughout the conference to the legal considerations of the breach of – and impetus to return to – the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit.

This included discussions about how the international legal frameworks should be updated for an “overshoot” world where countries would need to pursue “net-negative” strategies to bring temperatures down to 1.5C.

There were also discussions around governance of geoengineering technologies and the fairness and justice considerations that arise from the real-world impacts of breached targets.

The conference was being held just months after the ICJ’s advisory decision that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”.

IIASA’s Shleussner told Carbon Brief that the decision provided “clarity” that countries had a “clear obligation to bring warming back to 1.5C”. He added:

“We may fail to pursue it from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above.”

Prof Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford, insisted that “1.5C was very much alive and well in the legal world”, but noted there were “very significant limits” to what could be achieved through the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) – the global treaty for coordinating the response to climate change – both today and in the future.

Summarising discussions around how countries can be pushed to deliver the “highest possible ambition” in future climate plans submitted to the UN, Rajamani urged delegates to be “tempered in [its] expectations of what we’re going to get from the international regime”. She added:

“Changing the narratives and practices at the national level are far more likely to filter up to the international level than trying to do it from a top-down perspective.”

In a parallel session, Prof Christina Voigt, a professor of international law at the University of Oslo, pointed out that overshoot would require countries to aspire beyond “net-zero emissions” as “the end climate goal” in national plans.

Stabilising emissions at “net-zero” by mid-century would result in warming above 1.5C, she explained, whereas “net-negative” emissions are required to deliver overshoot pathways that return temperatures to below the Paris Agreement’s aspirational limit. She continued:

“We will need frontrunners. Leaders, states, regions would need to start considering negative-emission benchmarks in their climate policies and laws from around mid-century. There will be an expectation that developed country parties take the lead and explore this ‘negativity territory’.”

Voigt added that it was “critical” that nations at the UNFCCC create a “shared understanding” that 1.5C remains the “core target” for nations to aim for, even after it has been exceeded. One possible place for such discussions could be at the 2028 global stocktake, she noted.

She said there would need to be more regulation to scale up CDR in a way that addresses “environmental and social challenges” and an effort to “recalibrate policies and measures” – including around carbon markets – to deliver net-negative outcomes.

In a presentation exploring governance of solar radiation management (SRM), Ewan White, a DPhil student in environmental law at the University of Oxford, said the ICJ’s recent advisory opinion could be interpreted to be “both for and against” solar geoengineering.

Countries tasked with drawing up global rules around SRM in an overshoot world would need to take a “holistic approach to environmental law”, White said. In his view, this should take into account international legal obligations beyond the Paris Agreement and consider issues of intergenerational equity, biodiversity protection and nations’ duty to cooperate.

Dr Shonali Pachauri, research group leader at IIASA, provided an overview of the equity and justice implications that might arise in an overshoot world.

First, she said that delays to emissions reductions today are “shifting the burden” to future generations and “others within this generation” – increasing the need for “corrective justice” and potential loss-and-damage payments.

Second, she said that adaptation efforts would need to increase – which, in turn, would “threaten mitigation ambition” given “constrained decision-making”.

Finally, she pointed to resource consumption issues that might arise in a world of overshoot:

“The different technologies that one might use for CDR often depend on the use of land, water, other materials – and this, of course, then means competing with many other uses [of resources].”

A separate stream focused on loss and damage. Session chair Dr Sindra Sharma, international policy lead at the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, noted that the concept of loss and damage was “fundamentally transformed” by overshoot – adding there were “deep issues of justice and equity”.

However, Sharma said that the literature on loss and damage “has not yet deeply engaged with the specific concept of overshoot” despite it being “an important, interconnected issue”.

Sessions on loss and damage explored the existence of “hard social limits” under future overshoot scenarios, insurance and the need to bring more factors into assessments of habitability, including biophysical and social-economic constraints.

Communication challenges and next steps

At the conference, scientists and legal experts collaborated on a series of statements that summarised discussions at the conference – one for each research theme and an overarching umbrella statement.

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the statements represented a “key outcome of the conference” that could provide a “framework” to guide future research.

Nevertheless, he noted that statements are a “work in progress” and set to be “further refined” following feedback from experts not able to attend the conference.

At the time of going to press, the overarching conference statement read as follows:

“Global warming above 1.5C will increase irreversible and unacceptable losses and damages to people, societies and the environment.

“It is imperative to minimise both the maximum warming and duration of overshoot above 1.5C to reduce additional risks of human rights violations and causing irreversible social, ecological and Earth system changes including transgressing tipping points.

“This is required by international law and possible by removing CO2 from the atmosphere and further reducing remaining greenhouse emissions.”

Conference organisers also pointed delegates to an open call for research on “pathways and consequences of overshoot” in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The special issue will be guest edited by a number of scientists who played a key role in the conference.

Meanwhile, communications experts at the conference discussed the challenges inherent in conveying overshoot science to non-experts, noting potential confusion around the word “overshoot” and the difficulties in explaining that the 1.5C limit, while breached, was still a goal.

Holly Simpkin, communications manager at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, urged caution when communicating overshoot science to the general public:

“I don’t know whether ‘overshoot’ is an effective communication framing. It is an important scientific question, but when it comes to near-term action and the requirements that an ambitious overshoot pathway would ask of us, emissions are what are in our control.

“We could spend 10 more years defining this and, actually, it’s quite complex…I think it’s better to be honest about that and to try to be more simple in that frame of communication, knowing that this community is doing a wealth of work that provides a technical basis for those discussions.”

Experts: The key ‘unknowns’ of overshooting the 1.5C global-warming limit

Global temperature

|

08.10.25

State of the climate: 2025 on track to be second or third warmest year on record

Global temperature

|

29.07.25

Guest post: Why 2024’s global temperatures were unprecedented, but not surprising

Global temperature

|

18.06.25

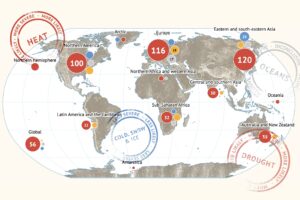

Mapped: How climate change affects extreme weather around the world

Attribution

|

18.11.24

The post Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

From Carbon Brief via this RSS feed